The Great Student-Led Learning Experiment

Last September, I had the good fortune to sit on a panel with my ShapingEDU colleagues to discuss student-led and flexible learning initiatives. There was much consensus regarding the pedagogy and possibility of these types of scenarios. As a panel, we shared our interpretations of the broad educational constructs that support students led learning initiatives. I was inspired by the conversation, but left wanting more in terms of practical application. I was resolute on the WHY but fuzzy on the how. Knowing no one-size-fits-all model exists, I went back to my lab (AKA Portfolio classroom) to conduct a series of experiments to gain more insight on the HOW of student-led learning initiatives.

I had recently started re-reading Stephen Covey's The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.

One key insights I found myself reflecting on was the idea that “there is no commitment without involvement.”

So I decided to begin this experiment asking a series of questions to elicit feedback from my students.

Full Sail has a very interesting class schedule. Unlike traditional college courses that run a full semester, our classes only last four weeks. Because of this pacing, I teach the same class 12 times a year, so the potential to glean key insights comes at the end of every month.

When asking my students what they would want out of student-led learning scenario, they said things like:

We wish we had more time...

We wish we could work on our own projects...

We wish we could learn more about...

We wish we could work with other students…

We wish we could slow down...

As the designer of this experiment, I wanted to know more specifically what they meant.

When they said they wish they had more time, they meant that they wish for time more wisely used. When they said they wanted to work on their own projects, what they were asking for was personal relevance. When they said they wanted to learn more, they were asking to follow their intellectual curiosities. When they said they wanted to work with other students, that was a cry for collaboration and when they said they wish they could slow down, what they were really wanting to do was focus.

With this wishlist in mind, my fellow Portfolio instructors and I designed an entire class, a full month, devoted to student pitched and student-led project based learning. All students were given the opportunity to pitch an idea for a project that they wanted to work on over a four week period of time. Students who pitched a project were then required to lead the project.

Not all students were required to pitch a project, but all students were required to self select into the teams they wished to support. Students could choose to contribute to more than one team, but were required to support at least one.

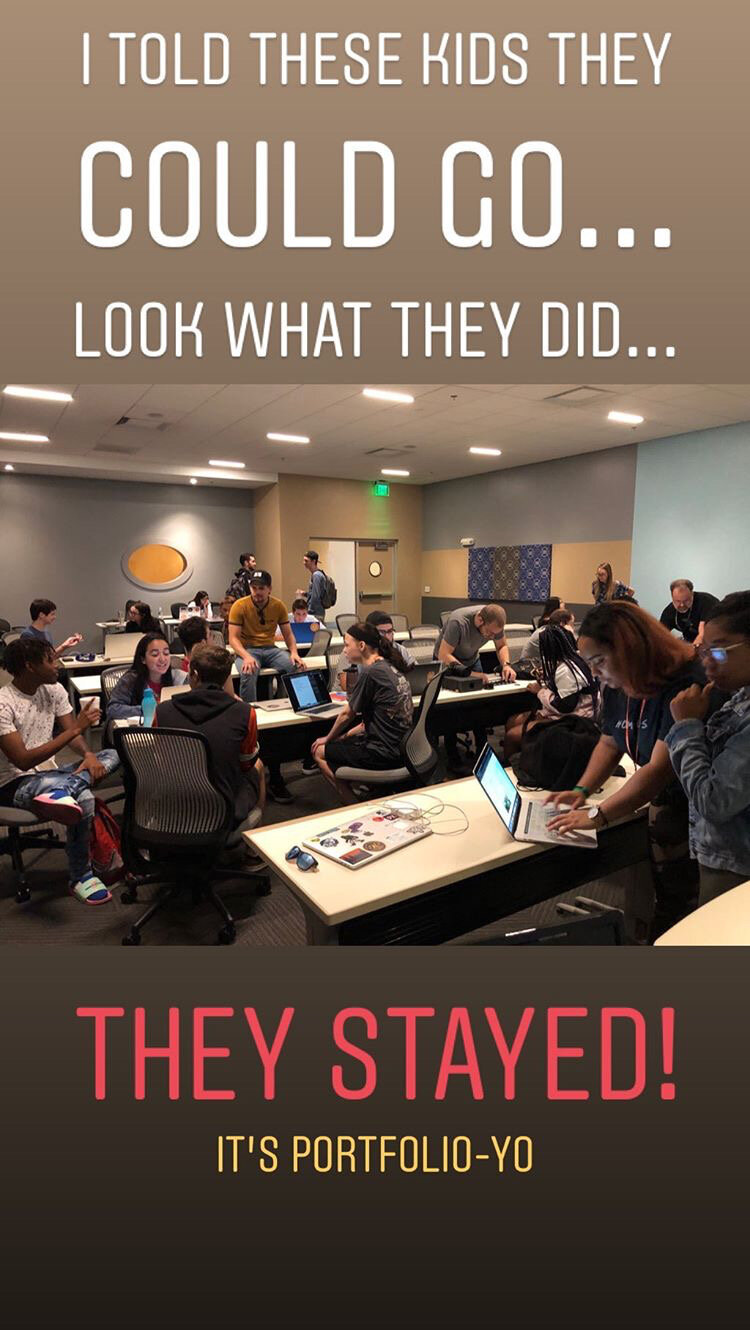

This initial test group was relatively small. Approximately 30 students participated. I estimate that number because there is an open door policy in our Portfolio classroom that allows students to stop by anytime - to collaborate, elicit feedback, or engage in mentorship. Three to four students regularly sit in on a class without officially being on the roster.

The structure that was defined on the outset of this experience was as follows:

You pitch the project, you lead it.

A clearly defined deliverable was required.

Accountability check-ins would occur each class session (2 per week).

Faculty mentors were available as requested.

In conceptualizing this experiment, the Portfolio team was concerned that perhaps students wouldn’t have any project ideas to pitch. To account for this possibility, we had several project ideas in our back pocket to fill the void as needed.

With this initial group, a total of nine projects were pitched, including two by faculty mentors. Projects ranged from producing a proof-of-concept for a complex music video shoot to a logo design challenge, and from a personal essay style writing project to the production of a short live action anime film.

As students pitched project ideas, faculty mentors asked clarifying questions to help determine a feasible scope of work and would paraphrase stated intent of each project to make sure all students were on the same page about what they’re signing up for.

Each of these projects had an agreed-upon deliverable that was to be completed within a four week period of time. The idea was not that these projects needed to be completely polished or finished in their totality, but rather that the students have a realistic goal of what was possible within the timeframe given their scope of work and the resources of their team.

Anecdotally, mid-point accountability checkins revealed a few insights. Students reported an appreciation for the autonomy and support they had to work on projects that were more relevant to them personally and professionally. They also liked the flexibility to work on more than one project. Additionally, students liked being able to participate at varying levels with different projects. That is, they appreciated being able to devote themselves significantly or minimally as needed or requested for the work. Lastly, students shared that this experience felt more collaborative, whereas more traditional group assignments felt competitive.

The results were overall positive, but we did experience some challenges along the way.

The autonomy that students had to choose which projects they wanted to contribute to also allowed them to overcommit. Because so many of the projects were fun and/or worthwhile, some students had trouble prioritizing their time. From a facilitation standpoint, this could be mitigated by limiting the number of groups students could support. However, the very necessary development of time management skills was also a desirable outcome.

Additionally, because some students were involved in multiple projects, conducting meetings during in-class time was tricky. If all groups were meeting simultaneously, there was no way to be present for all the conversations. From a facilitation standpoint, this could be mitigated by scheduling meeting blocks, so that all groups weren’t convening at the same time. However, the very necessary emergence of project management skills from the student leaders was also a desirable outcome.

Lastly, the energy and enthusiasm students had for this experience caused some to overestimate what was possible to deliver in the four short weeks of the Portfolio course. As such, some students had to adjust their expectations of what they would be able to produce to align with the time and talent they had on their team. From a facilitation standpoint, this was hard for faculty mentors to help mitigate. Some of the most lofty goals were achieved based on the connection and chemistry of a given team, while other seemingly more feasible goals were barely reached. In reflecting on why, it would seem that the necessary level of relevance was just never there.

Survey Says

At the close of this first round of the experiment, all students reached their desired outcome at some level. Students were asked to complete a survey to help gauge the success of the endeavor based on a few key considerations.

69% of respondents agreed that they used in-class time productively.

46% of respondents strongly agreed that they used their out-of-class time productively.

61% of respondents strongly agreed that there were enough accountability check-ins.

61% of respondents strongly agreed that there was enough mentorship from faculty.

61% of respondents strongly agreed that they were able to work on something personally or professionally relevant.

These questions were asked on a five-part Likert scale that spanned from strongly disagree to strongly agree. No respondents disagreed with any of the statements.

Additional anonymous comments included:

“Doing student-led projects was definitely my favorite Portfolio class.”

“I loved this month’s projects. I think it made it less stressful feeling like we were in control.”

“I liked being able to do what I wanted and what was relevant to my brand.”

“Being able to write for class helped with the flow of ideas for both the project and personal writing.”

Round 2

The results of Round 1 were undoubtedly positive. Even so, there were a few tweaks that we made going into Round 2. This go around, we had no faculty-sponsored projects, which allowed for even more dedication from faculty mentors. More coaching was offered on the front end to help account for some of the challenges we discovered midway through Round 1.

From the start, students were encouraged to:

Not overextend themselves;

Be mindful of a reasonable scope of work;

Prioritize time and commitments;

Regularly communicate with teammates; and

Utilize in class time for planning purposes and out of class time to execute their plans.

As we approached Round 2, one of the students who thoroughly enjoyed the experience in Round 1 opted to sit in on the class for the entire month. He actively supported other students with their projects and even led another one of his own. His presence and counsel seemed to help on-board this new crop of students to the idea and opportunity of student-led projects more quickly. Rafe was an advocate for this type of learning and his feedback was crucial in planning and executing Round 2.

For Round 2, we had approximately 30 students on the roster who pitched 11 different project ideas that ranged from designing an e-sports tournament to exploring photojournalism with film, and from creating a new media company to conducting a monster make-up photography shoot.

From a facilitation standpoint, we implemented block scheduling for team meetings so that individuals who were accountable to more than one group wouldn’t miss out on necessary information.

The challenges seen in Round 1 were still experienced in Round 2, despite preemptive coaching. Further conversation revealed that the students were once again really excited about all of the projects and not realizing how much time each one will take to execute. Some students felt overcommitted. Some project managers felt abandoned.

As an educator, while the creation of a polished deliverable suitable for one’s portfolio would be an ideal outcome, students learning how to prioritize their time and resources as well as be more proactive in their communication and efforts was equally desirable.

Throughout the experiment, faculty mentors recorded a few key observations:

Students discovered individual agency through the opportunity to pitch/lead their own projects.

Students rapidly developed leadership skills during the planning and execution of their goals.

Students elevated their technical skills through more relevant application of concepts and techniques.

Students strengthened personal and professional relationships through collaboration with peers.

Students established on-going support systems with faculty mentors.

In addition to seeing increased student engagement, faculty also reported feeling more purposeful in their mentorship and inspired to pursue some of their own creative work.

The experience was meaningful for both students and faculty alike and is a model we intend to run and study for several more rounds.